About this Series

This five-part series explores the craft of building Excel models with AI, from foundational skills to advanced techniques for developing full financial models.

- Tutorial 0: Introduction

- Tutorial 1: Decomposition

- Tutorial 2: Specification

- Tutorial 3: Iteration

- Tutorial 4: Verification

- Tutorial 5: Context and Collaboration

You've probably experienced this: you ask an LLM to build you a "complete acquisition model with debt sizing, a waterfall, and sensitivity analysis," and what comes back is... disappointing. The structure is awkward. The formulas don't quite work. The logic is inconsistent. You spend an hour trying to fix it and wonder if you should have just built the thing yourself.

Here's the problem: you tried to build everything at once.

This tutorial introduces the most important principle in working with LLMs to build Excel models—decomposition. Breaking complex models into pieces the LLM can handle well. It's not glamorous, but it's the difference between frustration and flow.

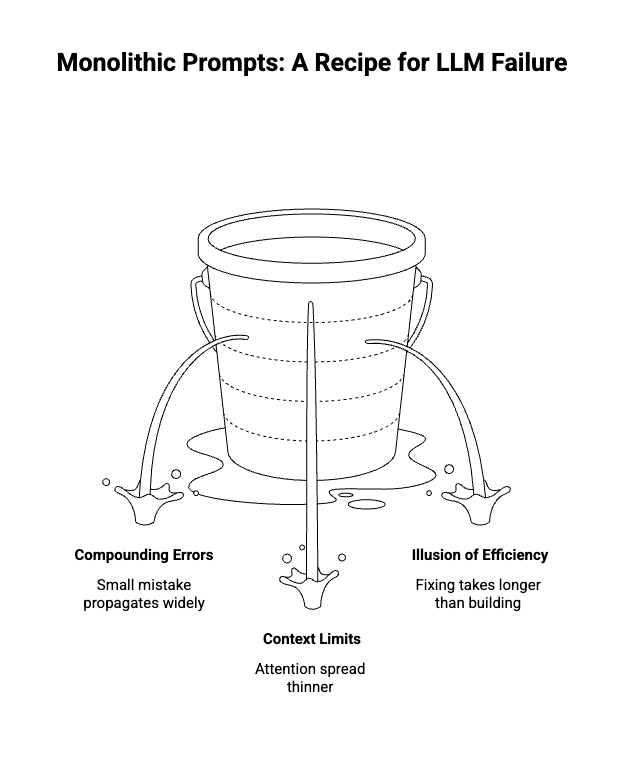

The Problem with Monolithic Prompts

When you ask an LLM to build a complete financial model in one shot, you're asking it to hold a lot of complexity simultaneously: the overall structure, the relationships between sections, the specific formulas, the time periods, the formatting, the edge cases. The LLM will attempt all of it. And it will partially succeed at all of it, which means it will fully succeed at none of it.

The compounding error problem. When the LLM makes a small mistake in the structure—say, putting debt service in the wrong section—every formula that references debt service is now wrong too. One early error propagates through the entire model. By the time you see the output, there are fifteen things to fix, and they're all tangled together.

The context problem. LLMs have limits on how much they can hold in their working memory. As your prompt gets longer and more complex, the LLM's attention gets spread thinner. Details from the beginning of your prompt start getting less weight. The model you get back is often strongest in whatever you mentioned last.

The illusion of efficiency. "But it's faster to just ask for the whole thing!" It feels that way. But count the time you spend trying to fix a broken monolithic output versus the time you'd spend building incrementally with prompts that actually work. The single prompt almost never wins.

The principle is simple: the LLM produces better outputs when each prompt has a focused, well-defined scope.

Vertical Decomposition: Sections of a Model

The most intuitive way to break up a model is by section—inputs here, calculations there, outputs at the end. This is vertical decomposition: slicing the model into layers.

The layers of a typical real estate model:

- Inputs and assumptions. Purchase price, square footage, rent per square foot, growth rates, hold period, exit cap. These are the dials someone turns.

- Property-level calculations. Revenue buildup, operating expenses, NOI. The core operating performance of the asset.

- Capital structure. Debt sizing, equity requirements, sources and uses. How the deal is financed.

- Cash flows. Period-by-period cash flows—operating cash flow, debt service, capital events.

- Returns and outputs. IRR, equity multiple, cash-on-cash. The answers the model exists to produce.

Build each layer as a standalone unit. When you ask the LLM to build the inputs section, that's all it's thinking about. It can do a good job because the scope is clear. When you move to property-level calculations, you can reference the inputs section: "Assuming the inputs are in cells B2:B15, build the revenue and NOI calculations."

Define the interfaces. Each section needs to know what it receives from the sections above and what it passes to the sections below. Make these explicit. "This section receives purchase price from B3, hold period from B5, and rent PSF from B7. It outputs Year 1 NOI in cell E25." When the interfaces are clear, the sections can be built independently and will connect correctly.

Start with the dependency map. Before you write any prompts, sketch out what depends on what. You can't build debt service until you have debt sizing. You can't have debt sizing until you know the purchase price and LTV. You can't calculate returns until you have all the cash flows. This map tells you the order to build in.

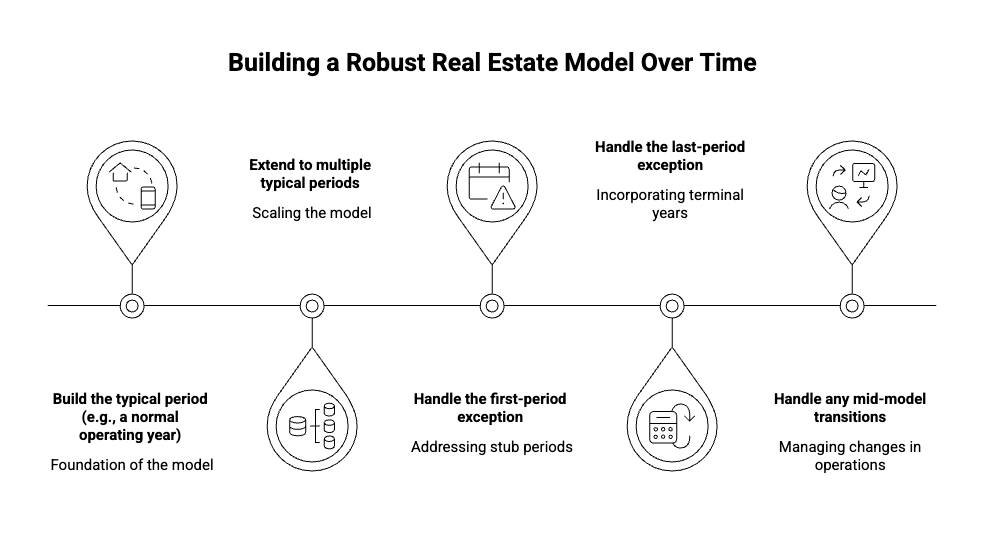

Horizontal Decomposition: Time and Repetition

Real estate models extend across time—five years, ten years, monthly periods during construction. This is the horizontal axis: period 1, period 2, period 3, and so on.

The "first column" principle. Get one period working perfectly before you extend to multiple periods. If your Year 1 cash flow calculation is right—revenue minus opex minus debt service, all referencing the correct cells—then copying it across to Years 2-10 is trivial. If Year 1 is wrong, you'll have wrong formulas copied ten times, and fixing them is ten times the work.

This principle applies at every level. Get one month working before building twelve months. Get one draw schedule period working before extending through construction. Get the first year of a waterfall tier working before copying across the hold period.

Handle exceptions explicitly. Time-based models often have periods that behave differently:

- Stub periods. An acquisition on March 15 means the first year isn't a full year.

- Terminal years. The final period includes a sale, which changes the cash flow structure.

- Construction to stabilization. The model behaves differently during construction, lease-up, and stabilized operations.

- Transition periods. Monthly during construction, annual during operations.

Don't expect the LLM to handle these exceptions automatically. Call them out explicitly. "Build Year 1, which is a stub period starting April 1. Then we'll handle the full years separately. Then we'll handle the terminal year with the sale."

The sequence:

- Build the typical period (e.g., a normal operating year)

- Extend to multiple typical periods

- Handle the first-period exception

- Handle the last-period exception

- Handle any mid-model transitions

Logical Decomposition: Separating What from How

There's another axis of decomposition that's less obvious but equally important: separating the goal from the implementation.

When you ask "build me a debt service calculation," you're conflating two things: what you want to achieve (calculate the periodic payment on the loan) and how to achieve it (the specific Excel formula, the cell references, the structure). The LLM has to figure out both simultaneously, and that's where misalignment creeps in.

First prompt: define the goal. "I need to calculate debt service for a 5-year interest-only loan that converts to 25-year amortization in year 6. The loan amount is in B10, the interest rate is in B11. Help me think through how this should be structured."

Now you're having a conversation about the logic. The LLM can focus on the financial mechanics without also worrying about Excel syntax. You'll catch misunderstandings here—maybe you meant the loan converts to amortization at year 3, not year 6. Better to catch that before any formulas are written.

Second prompt: define the structure. "OK, let's structure this as three rows: one for the interest-only debt service, one for the amortizing debt service, and one that selects the right one based on the period. Where should each row go, and what should the column headers be?"

Now you're aligning on architecture. You'll see if the LLM is putting things where you want them. You might realize you also need a row for the loan balance, or that the structure should be different.

Third prompt: implement the mechanics. "Great. Now write the formulas for each of those three rows. Interest-only debt service should be in row 25, amortizing debt service in row 26, the selector in row 27. The period number is in row 3."

Now the LLM can focus purely on Excel mechanics, with all the context established. The formula it writes is much more likely to be correct because all the ambiguity has been resolved in the earlier prompts.

Why this works: Each prompt has a single cognitive focus. Goal. Structure. Implementation. Mixing them creates confusion; separating them creates clarity.

Sequencing Strategies

Decomposition creates a bunch of pieces. Sequencing is the order in which you build them. The right sequence makes each step easier; the wrong sequence creates dependency problems.

The standard sequence for most models:

- Structure first. Build the skeleton—row labels, column headers, section organization—before any formulas. This is cheap to change. Formulas that reference the wrong structure are expensive to fix.

- Logic second. Once the structure is set, build the formulas section by section. Work in dependency order: inputs first, then calculations that use inputs, then calculations that use those calculations.

- Formatting third. Don't think about colors, fonts, number formats, or borders until the logic works. Formatting is fast to apply once; reformatting after every logic change is tedious.

- Edge cases last. Get the model working for the typical case first. Then handle the stub period, the zero-input scenario, the refinancing toggle. Edge cases are important, but they're also where you can sink infinite time. Get the core working first.

Alternative sequences for specific situations:

- For unfamiliar model types: Start with the outputs and work backward. "I need to produce an IRR, equity multiple, and cash-on-cash return. What cash flows do I need? What calculations produce those cash flows? What inputs drive those calculations?" This ensures you build only what's needed.

- For complex interdependencies: Build a simplified version of the entire model first, then add complexity. A waterfall with one tier before a waterfall with four tiers. Annual periods before monthly periods. One scenario before a sensitivity table.

- For modifications to existing models: Isolate the part you're changing. Understand its inputs and outputs. Build the replacement, test it standalone, then integrate.

Handling circular dependencies. Sometimes A needs B and B needs A. Debt sizing might depend on equity returns, which depend on debt sizing. Two approaches:

- Break the loop with an initial assumption. "Assume debt is $10M for now. Build the equity cash flows. Then we'll come back and size the debt properly."

- Build both pieces with placeholders. Get the structure and logic of both sections working with hardcoded numbers, then connect them and enable iteration.

A Worked Example: Decomposing an Acquisition Model

Let's say you need to build a multifamily acquisition model from scratch. Here's how decomposition applies:

Step 1: Map the dependencies.

- Returns need cash flows

- Cash flows need NOI and debt service

- NOI needs revenue and expenses

- Debt service needs loan terms and loan amount

- Loan amount needs purchase price and LTV

- Everything needs the inputs

So the order is: inputs → property operations → debt → cash flows → returns.

Step 2: Build structure first.

Prompt: "I'm building a 10-year multifamily acquisition model. Create the structure—section headers, row labels, column headers for years 1-10—for these sections: Inputs & Assumptions, Revenue, Operating Expenses, NOI, Debt, Cash Flows, Returns. Don't write any formulas yet, just the skeleton."

Now you have a layout to work within.

Step 3: Build inputs.

Prompt: "In the Inputs section, I need: purchase price, units, avg rent/unit/month, rent growth rate, vacancy rate, opex per unit, opex growth rate, LTV, interest rate, amortization, hold period, exit cap rate. Set these up as labeled input cells."

Step 4: Build revenue.

Prompt: "Build the Revenue section. It should show gross potential rent (units × rent × 12), vacancy loss, and effective gross income for each year. Rent should grow by the rent growth rate each year. Reference the inputs we created."

Step 5: Continue section by section. Operating expenses. NOI. Debt sizing. Debt service. Cash flows. Returns. Each prompt is focused, references what's already built, and produces a manageable chunk to verify.

Step 6: Handle edge cases. The exit year includes a sale. Year 1 might have a stub. Maybe there's a renovation in year 2. Address each of these specifically after the core model works.

Common Mistakes in Decomposition

Going too granular. If every cell is a separate prompt, you'll spend more time prompting than modeling. Find natural chunk sizes—a section, a calculation block, a set of related formulas. Usually 10-30 cells per prompt is about right.

Going too broad. If your prompt is more than a paragraph and asks for multiple sections, you're probably back in monolithic territory. A good prompt can usually be stated in 2-3 sentences.

Building out of order. If you find yourself saying "assume this will come from somewhere," you might be building the wrong section. Step back and identify what should be built first.

Skipping the structure pass. It's tempting to just ask for the formulas. But formulas without clear structure end up in awkward places. Spend the time to get the layout right.

Not defining interfaces. If you don't tell the LLM exactly where inputs come from, it will guess. Sometimes it guesses right. Often it doesn't, and now your formulas reference nonexistent cells.

Practical Exercises

Exercise 1: Dependency mapping. Take a model you've built before—a pro forma, a DCF, anything. Draw the dependency map. What needs to be built first? What comes last? Are there any circular dependencies?

Exercise 2: Chunk identification. Take the same model. If you were going to build it with an LLM, how many prompts would you use? What would each prompt produce? Can you describe each chunk in 2-3 sentences?

Exercise 3: Sequencing comparison. Try building a simple model (just inputs and a basic cash flow) two ways: all at once in a single prompt, and decomposed into structure → logic → formatting. Compare the quality of outputs and the total time spent including revisions.

Key Takeaways

- The LLM works best with focused, well-scoped prompts. Monolithic "build everything" prompts produce mediocre, error-riddled outputs.

- Decompose vertically by section. Inputs, calculations, outputs. Build each as a standalone unit with clear interfaces.

- Decompose horizontally by time. Get one period working, then extend. Handle exceptions (stub, terminal, transition) explicitly.

- Decompose logically by what vs. how. Clarify the goal before implementing the mechanics. Separate structure from formulas from formatting.

- Sequence matters. Build in dependency order. Structure before logic before formatting before edge cases.

- Find the right chunk size. Big enough to make progress, small enough for the LLM to handle well. Usually 10-30 cells per prompt.

Decomposition isn't about working slower. It's about working in a way that actually succeeds. The time you save on failed iterations and broken formulas far exceeds the time spent breaking the problem into pieces.

Next in the series: Specification—Closing the Gap Between Your Mind and the Model.

About Apers AI

Apers AI was founded by researchers from Harvard, Yale, and MIT with backgrounds in quantitative asset pricing and institutional real estate. Our mission is to advance the science of capital deployment by applying autonomous agents and machine reasoning to real asset markets.